The Uncredited Collaboration Behind The New Yorker's Iconic 9/11 Cover

Within hours of the attack, Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman went to work to create the famous black-on-black image—that almost didn't happen.

On September 11, 2001, after witnessing an airplane crash into one of the Twin Towers, Françoise Mouly faced two imperative tasks: First, she had to find her kids, and then she had to come up with a New Yorker cover to somehow mark the event.

That day, Mouly and her husband Art Spiegelman, the cartoonist best known for his graphic memoir Maus, were walking out of their SoHo loft, just 10 blocks north of the World Trade Center, planning on voting in the city’s Democratic mayoral primaries, when they saw the first plane hit the North Tower. Mouly, who's been the art editor of the New Yorker since 1993, initially assumed it was an accident, a leisure plane going off course maybe—it was the only thing that made sense. What she calls her “journalist’s instincts” kicked in, and she called David Remnick, the editor of the New Yorker since 1998, and told him to turn on his TV.

The couple’s daughter, 14-year-old Nadja, had just started classes at Stuyvesant High School, four blocks from the towers. Worried that debris might land on the school, the anxious parents rushed to find her. Locating her wasn’t easy—the 10-story school building housed more than 3,500 students. While they searched, Spiegelman overheard a Spanish-language report from a janitor’s radio saying that the Pentagon had been attacked. Then the lights went out, and the building trembled from the collapse of the South Tower. Spiegelman was sure they would all die in the school. After continuing to search for an hour and a half, they found Nadja. As they were leaving Stuyvesant, the North Tower crumbled behind them.

Their daughter in hand, the couple then raced to find their 10-year-old son, Dash, who attended the United Nations International School further uptown. “I was willing to live through the disaster wherever it took me, as long as we were all together as a family unit,” Spiegelman later explained to the New York Times. Once Dash was recovered and the family was safely ensconced in their loft, they checked their messages. Among various reports from friends on their safety, Mouly says, there were also “messages from the New Yorker saying, ‘Get your ass over here. We want to do a cover.’”

Spiegelman, then a staff artist for the magazine with many covers under his belt, went to work in his studio, a few blocks from their loft. The next day, Mouly found a friend to stay with the kids and went into the New Yorker’s midtown office to face the impossible task of coming up with an appropriate cover. She remembers thinking, “I want no image. I can’t do this. No image can do justice to this.” Mouly explained her dilemma to a neighbor, a fellow mother, who responded by saying, “What, you have to go to work to do a magazine cover? That’s ridiculous! I’ll tell you what you do: no cover.”

Spiegelman, meanwhile, was making an image that contrasted the lovely fall weather of that day with the horrible event that happened, with the towers covered in a Christo-like black shroud against a Magritte-style blue sky. Every time he walked between his studio and the loft, Spiegelman would look where the towers had stood. Like a phantom limb or a ghostly presence, they were both there and not there, felt but invisible. Remnick, for his part, was considering the use of a photograph—it would have been the first time in New Yorker history and a precedent-breaking way to register such an immense historical event.

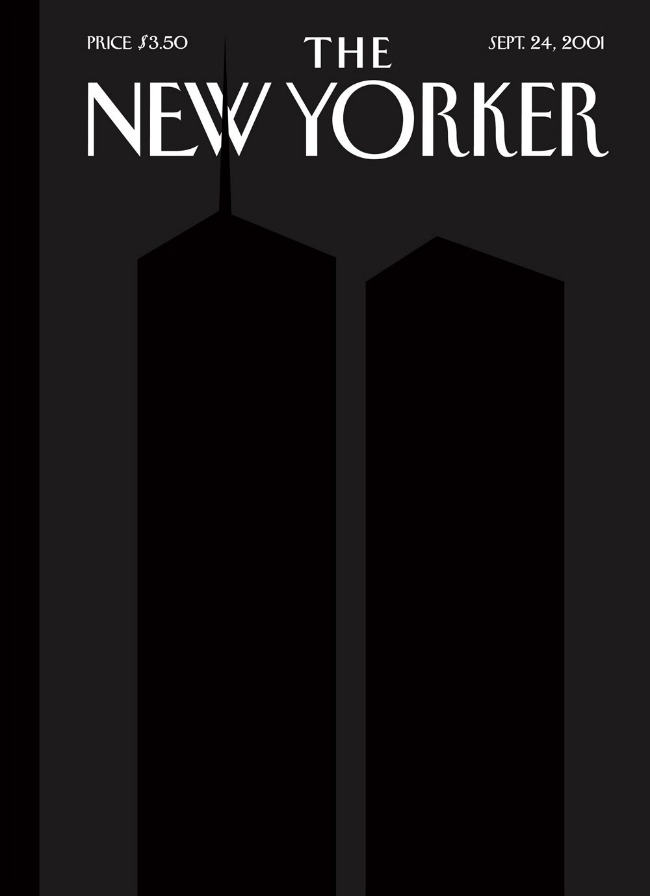

Neither idea appealed to Mouly. She still felt that no image—painting, drawing or photo—could do justice to what she and the rest of New York had just experienced. She had another idea: What about an all-black cover? A cover that, as per her neighbor’s argument, wasn’t a cover. Spiegelman wanted his image to run but thought that if the New Yorker was going that route, it should be combined with his own suggestion: How about a silhouette of the towers against a black background, black on black? “That actually felt like the most creative solution,” Mouly says now. She drew up a cover based on their ideas. “When I saw it, even before I presented it to my editor, I was like ‘Oh my god, this actually is the answer, the negative answer, to what I was looking for because it is such a strong statement.’”

When she showed Remnick the image, he asked who did it. Even though she had drawn it, Mouly, driven by her desire to see the image published, says she didn’t want to admit she’d done it—she was worried because she wasn’t a “name” artist. Besides, the New Yorker’s tradition at that time was not to give collaboration credits on covers. (Mouly changed that later in 2001, giving dual credit to Rick Meyerowitz and Maira Kalman for “New Yorkistan,” thereby establishing a new precedent.) Unprepared for an answer, and used to contributing her ideas to the artists she worked with, Mouly gave Spiegelman the credit—it was his idea, after all. Initially, Spiegelman didn’t want to put his name on it. As he explained in an interview with a New York public television station, “It was only when I saw the proof that I went, ‘Oh, gee, I had nothing to do with that, but it’s really good.’ So I don’t feel like I made it. It was just sort of a product of trying to assimilate those two days.”

There were a few last-minute hitches before the cover ran. Late Thursday night, rumors circulated that another magazine might also be doing a black cover. Mouly argued that her cover wasn’t just black but contained a subtle image that set it apart. Fortunately, word came back that the other weekly was going with a photo cover. By Thursday, Mouly finally had Greg Captain, her trusted prepress expert, on the premises. Because of the subtle effect the cover had to achieve, Mouly scrambled to work with her prepress crew to make sure that the ink densities were sufficiently different to capture the contrast between the two almost identical shades of black.

The prepress work was made more complicated by the fact Captain had been in Chicago on 9/11; because flights were cancelled after the terrorist event, Captain had to drive back to New York to help solve the technical problems. Then, on Friday morning, he drove the almost 15 hours to the printer in Kentucky with four versions of the cover, watching the press all night to make sure it worked before driving back. The 9/11 cover is now among the most famous images in the history of the New Yorker and one of the few lasting works of art to come out of the destruction of the Twin Towers. The image works almost like an optical illusion. At first glance it does seem to be all black. Only when you catch the cover at a certain angle do the dark shapes of the Twin Towers emerge from the inky background. “Once you saw it, it was like a ghost,” Mouly explains. “It captured this kind of disconcerted feeling. Everyone was lost and so was I. I was lost in a land where there could be no image. The fact that this negative image still managed to be an image was what really reconciled me to what I do. It showed how powerful simplicity of means could be.”

Art Spiegelman was the President of the Angoulême Comics Festival in 2012 (in effect, a guest of honour who helps organize the show and is celebrated with a special exhibition). When the origins of the 9/11 cover were explained to the French Minister of Culture Frédéric Mitterrand, who was looking at a large-size print, he responded by calling it “une idée de génie.” It’s true that the idea is genius, but so is the execution. It was a true example of collaborative art. Many of the hallmarks of Mouly’s tenure as New Yorker art editor can be seen in the 9/11 cover, including a direct engagement with current events—an enormous tonal shift in New Yorker cover history. But the cover doesn’t deal with this tragedy in the didactic manner of, say, a political cartoon, but rather through artful means: using subtlety and ambiguity, strong design, a compelling use of color (or in this case, a memorable absence of color) and the distillation of experience (rather than ideas or ideologies) into an iconic image. The dialogue between Mouly and Spiegelman was also typical of the strongly collaborative way she always has worked with, and continues to work with, her artists.

I asked Mouly why she’s only recently been willing to talk about her accomplishments as an editor, not just on the 9/11 cover but her wider achievements both at the New Yorker and her earlier tenure as co-editor of RAW (a hugely influential avant-garde comics magazine she and Art Spiegelman edited from 1980 to 1991).

“In the past two or three years, I have started using the first person, calling myself an artist,” Mouly says. “The courage for it came from, first, the success of RAW, then the new-found confidence and peace I made with myself when I became a mother, and a sense of accomplishment at the New Yorker—I do believe I’m harnessing the power of artists as catalysts, holding a mirror to society, producing a suite of images, that, taken as a whole, capture what we’re going through... And, finally, the 9/11 cover. In the three or four days after the tragedy, I pursued my guts’ feelings in spite of everyone else’s agenda. It was a terrifying moment... I was utterly lost, yet I had the responsibility of coming up with a statement. I had to buck everyone else’s idea of what I should do—editors who wanted a photo and Art who wanted his own image published. But I’m glad I made that leap of faith in myself.”

This post is adapted from In Love With Art: Françoise Mouly's Adventures in Comics With Art Spiegelman.